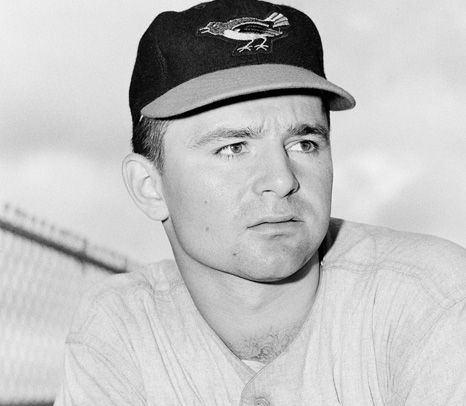

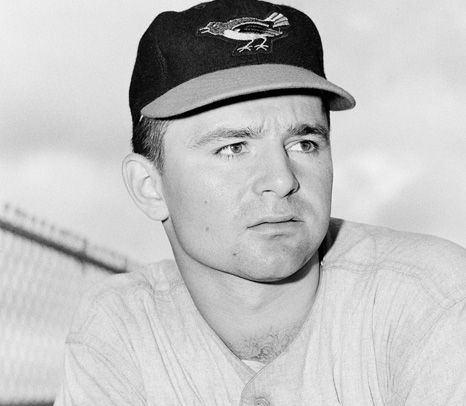

Remembering Steve Dalkowski

Age 80, New Britain, Conn.

Passed away on April 19, 2020

Steve Dalkowski, who entered baseball lore as the hardest-throwing pitcher in history, with a fastball that was as uncontrollable as it was unhittable and who was considered perhaps the game’s greatest unharnessed talent, died April 19 at a hospital in New Britain, Conn. He was 80.

His family announced his death in a death notice in the Hartford Courant, which reported that he had covid-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus.

Mr. Dalkowski pitched nine years in the minor leagues in the 1950s and ’60s, mostly in the Baltimore Orioles organization, without reaching the major leagues. Yet, in that time, he amazed — and terrified — countless hitters with a blazing fastball of astonishing speed.

He was not a big man, only about 5-foot-10 and 175 pounds, but he possessed lightning in his left arm. He had almost a slingshot motion, somewhere between a sidearm and overhand delivery.

Ted Williams, who played against Bob Feller and other fireballers during his Hall of Fame career, was said to have faced Mr. Dalkowski in one spring training and called him the “fastest ever.” Another major leaguer, Eddie Robinson, swung and missed at 10 pitches before he could make weak contact with one of Mr. Dalkowski’s fastballs.

“As 40 years go by, a lot of stories get embellished,” Pat Gillick, Mr. Dalkowksi’s minor league teammate and a Hall of Fame general manager, told Sports Illustrated in 2003. “But this guy was legit. He had one of those arms that come once in a lifetime.”

Mr. Dalkowski was prominently featured in Tim Wendel’s 2010 book, “ High Heat: The Secret History of the Fastball and the Improbable Search for the Fastest Pitcher of All Time.”

The fastest documented fastball in baseball history was thrown by left-hander Aroldis Chapman, currently a relief pitcher for the New York Yankees. Chapman had the speed tattooed on the inside of his left wrist: 105.1 mph.

People who saw Mr. Dalkowski pitch said he threw at least as hard. Radar guns were not in use when Mr. Dalkowski pitched, but his catcher in the Orioles system, Cal Ripken Sr., estimated his fastball was between 110 and 115 mph.

Ripken spent decades in baseball, eventually becoming manager of the Orioles. He saw Sandy Koufax, Goose Gossage and J.R. Richard pitch, and he watched from the third-base coach’s box as Nolan Ryan threw fastballs clocked at more than 100 mph.

“Steve Dalkowski was the hardest thrower I ever saw,” Ripken said.

In one game Ripken was catching, he called for a breaking pitch. Mr. Dalkowski missed the sign and threw his fastball instead. It hit the umpire in the mask, breaking it in three places. The umpire was knocked unconscious.

In 1957, when Mr. Dalkowski was 18 and in his first professional season, he tore off part of a batter’s ear with an errant pitch. That batter was Bob Beavers, then in the Dodgers organization.

“The first pitch was over the backstop. The second pitch was called a strike, I didn’t think it was,” Beavers told the Courant last year. “The third pitch hit me and knocked me out, so I don’t remember much after that. . . . I never did play baseball again.”

That was Mr. Dalkowski’s problem throughout his baseball career: He had the best arm in the game, but he could not control his pitches.

In high school, he pitched a no-hitter in which he walked 18 batters and struck out 18. Another time, in an extra-inning minor league game, he walked 18 hitters and struck out 27 while throwing 283 pitches — far more than a team would allow a pitcher to throw today.

In 1960, when he was with a minor league team in Stockton, Calif., Mr. Dalkowski struck out 262 batters in 170 innings — an astonishing rate of 14 strikeouts per 9 innings. But he also walked 262 batters.

His pitches sometimes flew over backstops and sent spectators ducking for cover. On a dare, he threw a ball over the center field fence — 440 feet away. Another time, he won a bet with teammate Andy Etchebarren and fired a ball through a wooden fence.

He once beaned a mascot with a fastball — a scene depicted in the 1988 baseball movie “Bull Durham.” The film’s screenwriter, Ron Shelton, played in the Orioles’ minor league system a few years after Mr. Dalkowski, but stories about him were still being told. He based the character of Ebby Calvin “Nuke” LaLoosh, played by Tim Robbins, on Mr. Dalkowski.

“Playing baseball in Stockton and Bakersfield several years behind Dalko, but increasingly aware of the legend,” Shelton wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 2009, “I would see a figure standing in the dark down the right-field line at old Sam Lynn Park in Oildale, a paper bag in hand. Sometimes he’d come to the clubhouse to beg for money.

“Our manager, Joe Altobelli, would talk to him, give him some change, then come back and report, ‘That was Steve Dalkowski.’ And a clubhouse full of cocky, young, testosterone-driven baseball players sat in awe -- of the unimaginable gift, the legend, the fall.”

In Pensacola, Fla., in 1959, two of his teammates were Steve Barber and Bo Belinsky, both hard-throwing and hard-drinking left-handers. Mr. Dalkowski threw harder and drank harder than both of them.

“When I roomed with him, I roomed with a suitcase,” his roommate Herm Starrette told the Baltimore Sun in 1999. “He was a nice guy, a young kid who hadn’t matured, and he just didn’t know what time of day it was as far as coming in at night. He came in when he got tired of being out, let’s put it that way.”

Coaches tried everything with Mr. Dalkowski: changing his stance on the mound, his grip on the ball; asking him to aim high or aim low, to relax as he threw. Nothing worked. AD

In 1962, Mr. Dalkowski was assigned to the Orioles’ Class A affiliate in Elmira, N.Y. The manager was a young Earl Weaver, who later managed in Baltimore for 17 years and went into the Hall of Fame.

Weaver encouraged Mr. Dalkowski to throw his slider for strikes and not to throw his fastball at full strength every time. When he got to two strikes on an opposing hitter, Weaver would whistle, as a signal for Mr. Dalkowski to bring his best fastball.

“Earl had managed me in Venezuela in winter ball. We got along,” Mr. Dalkowski told the Sun in 2003. “He handled me with tough love. He told me to run a lot and don’t drink on the night you pitch. Then he gave me the ball and said, ‘Good luck.’ ”

Earl Weaver, Hall of Fame Orioles manager, dies at 82

Mr. Dalkowski would go on to have his best season, with an earned run average of 3.04. He had 37 consecutive scoreless innings at one point and finished with 192 strikeouts in 160 innings. His 114 walks marked the first time he had allowed less than one walk per inning.

The next year, in spring training, Mr. Dalkowski was fitted for a big league uniform, finally about to realize his dream.

“He had the team made easily,” Orioles manager Billy Hitchcock told the Sun years later.

But on March 22, 1963, while pitching against the New York Yankees in a spring training game, Mr. Dalkowski felt something snap in his elbow. He was 23.

He tried to come back from the injury, pitching in the minors until 1965, but the lightning was gone. During his minor league career, he won 46 games and lost 80. In 956 innings, he struck out 1,324 batters and walked 1,236.

He never made it to the majors.

Steven Louis Dalkowski Jr. was born June 3, 1939, in New Britain. Both parents were factory workers.

From an early age, Mr. Dalkowski excelled in sports. He was the quarterback of the New Britain High School football team and, of course, the ace pitcher in baseball.

His high school catcher, Len Pare, told the Sun in 2003 what it was like to be behind the plate when Mr. Dalkowski was pitching.

“The ball would almost hit the ground after he threw it,” Pare recalled, “but it would rise and rise, and by the time it got to the plate, I’d be jumping up to catch it.”

“It came in so hard that it made a loud buzzing sound,” his junior high school coach, Vin Cazzetta, told the Sun. “He was already a phenom by the time he got to me. No one wanted any part of him.”

After his elbow injury in 1963, Mr. Dalkowski disappeared for years. He became a migrant farmworker in California — and a down-and-out alcoholic. He was married and divorced twice.

In the 1970s, a former teammate persuaded him to enter a rehabilitation program and helped him find a landscaping job. But at the first opportunity, he said, Mr. Dalkowski started drinking again.

After other failed rehab attempts, Mr. Dalkowski’s sister, Patricia Cain, brought him back to New Britain in 1994. He spent the rest of his life in an assisted-living facility, within blocks of the high school baseball field where he first found glory. She is his only immediate survivor.

Mr. Dalkowski had alcohol-related dementia, but in interviews he could still recall his baseball teammates and details of games decades in the past — and he never lost the grip on his fastball. He rose from a wheelchair last year in Los Angeles to throw out a ceremonial first pitch at Dodger Stadium.

“It’s the gift from the gods — the arm, the power — that this little guy could throw it through a wall, literally, or back Ted Williams out of there,” Shelton wrote in 2009.

“That is what haunts us. He had it all and didn’t know it. That’s why Steve Dalkowski stays in our minds. In his sport, he had the equivalent of Michelangelo’s gift but could never finish a painting.”

Say something about Steve...